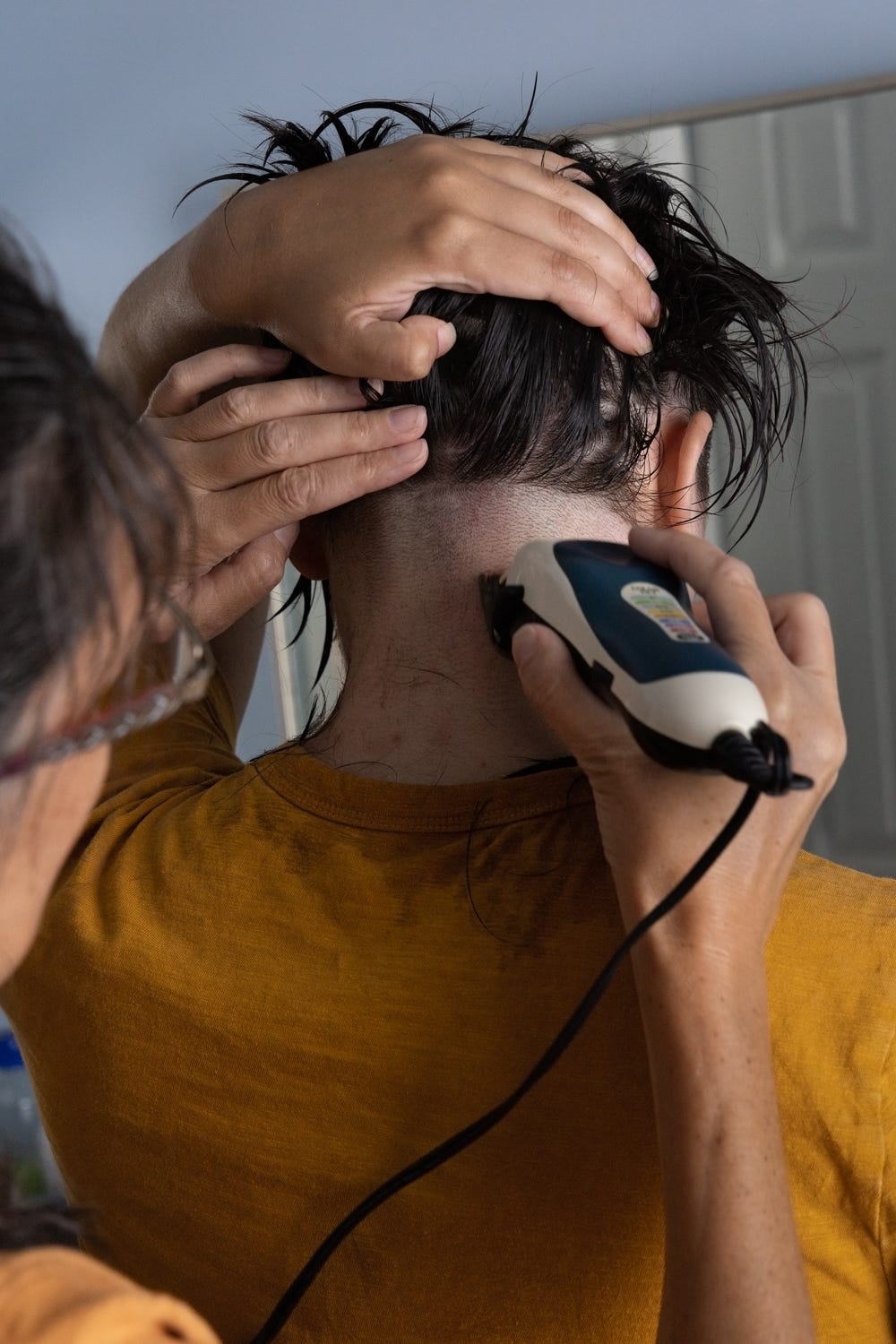

Clippers glide against my skull, relieving my scalp of the constant pressure it feels from the presence of hair, letting the air revitalize skin. My mom and I chat as she tilts my head to the side, cool fingers pressing lightly on my occipital ridge. I treasure these moments between us, the laughing joke of false impatience as my mom waits for me to readjust the camera, the way she smiles when I get excited over the images upon review.

My mom has been cutting my hair since I was 15 years old and wanted an undercut. I didn’t call myself gender-fluid then, though I had a massive crush on Ruby Rose and knew something about their description of gender felt right in my body. Whenever I went to salons as a kid I typically left disappointed, having spent much of the time pushing the hair stylists to cut my hair shorter, more masculine, less soft layers and more hard lines, only to leave with too much hair on my head.

Hair has always been a source of self expression and a source of frustration for me. As someone with sensory issues, I begin to get the urge to shave part of it as soon as I can feel the weight of it. The way that long hair rounds my face and softens the edge of my jaw can induce gender dysphoria, the person in the mirror somehow not quite me. At the same time, I look fondly at the images of me in college, hair to my waist, the fullness of it giving the hairdresser pause when I went to have it cut after 5 years of growth.

It took my mom a long time to try an undercut after commenting on how comfortable mine looked for years. I created lines that complimented the sharp geometry of my mother’s face, cut away the hair ends that were the source of frustration, and helped her style it after. A reciprocity of care flowed between us through home haircuts.

I first began this series during the pandemic, documenting the first time I wanted an undercut again since college. It was only a few weeks into lockdown, but over a year of my living back with my parents after experiencing a health crisis. I credit this image with changing the trajectory of my life-I submitted it to the first Life at Six Feet call and joined the community as a founding member soon after. After a series of unlikely events, I find myself living in North Carolina with the friends I made through Life at Six Feet.

As time went on in the pandemic and things in our household became increasingly unstable, haircuts became not only a marker of time, but a moment of care, stillness imposed upon us by sharp scissors and the carefulness of holding a razor. Things were complicated, but hair cutting was a simple exchange between us.

Interdependence has become something I value, something I continue to work towards valuing. I was first introduced to this idea through Disability Visibility, edited by Alice Wong. In those early days of the pandemic, I was struggling with the fallout of losing my bodily autonomy to the medical system and to illness. More than that, I was struggling with the loss of an idea I had about myself, the narrative I’ve come to recognize as a struggle for me to disrupt. I put independence and being needless on a pedestal, only to come to the shocking realization that I am human and sometimes require care.

There is such strength in interdependence, a beauty in the vulnerability of care. My relationship to care has changed drastically since that time, having stepped more deeply into care roles within the disability community in my own life. Realizing that individual independence is a myth-we all are where we are because of acts of care that have occurred whether we recognize (or realize) them or not-has radically changed the way I view the world. Though I admit it is often more difficult to apply this world-view to myself.

I first started asking my mom for help with my hair because I have historically had extremely weak shoulders. Being hypermobile, my shoulders frequently slip out of place-it has taken many years of physical therapy to gather the level of function I have in them. I never learned to french braid because I could never hold my arms up and my neck in that position for long enough to gather my hair into plaits. Shaving my head seemed like an incredibly daunting task.

When I shaved my head during the pandemic, my mom stepped in to help once my arms grew tired, the numbness of pinched nerves creeping along my forearms. I realized I didn’t feel ashamed about asking for help-I valued the time spent close together, hands pressed to scalp. Being able to offer a simple haircut in return seemed like a reciprocity, something that as an adult I could give back to my mother, something that spoke a language that encapsulated our shared experiences.

In this ritual of hair cutting, gender would invariably come up. I don’t speak a lot about gender in my day to day life-though I’ve been out for half of a decade, I find myself still struggling with a childhood of fearful concealment. In these moments between us however, my mom and I talk about the ways hair contributes to my comfort in my body, her own challenges with gender expectations, the non-conformity that we both share, how neurodivergence changes the way we see ourselves fitting into the world.

I started cutting my own hair when I moved into my current home. Finding a physical therapist who specializes in hypermobile bodies has meant that I can use my shoulders more functionally. I can put dishes away above my head, I can hold a mirror and a razor to shave the back of my head. Whenever my mom and I are together though, we perform this ritual, and I make some photographs.

This project is beginning to expand, slowly. I invited my friend Kaoly Gutierrez to make self portraits with me last year as she cut my hair. There was something new in the experience, something healing. I want to invite more friends to cut my hair, and maybe offer them something in return.