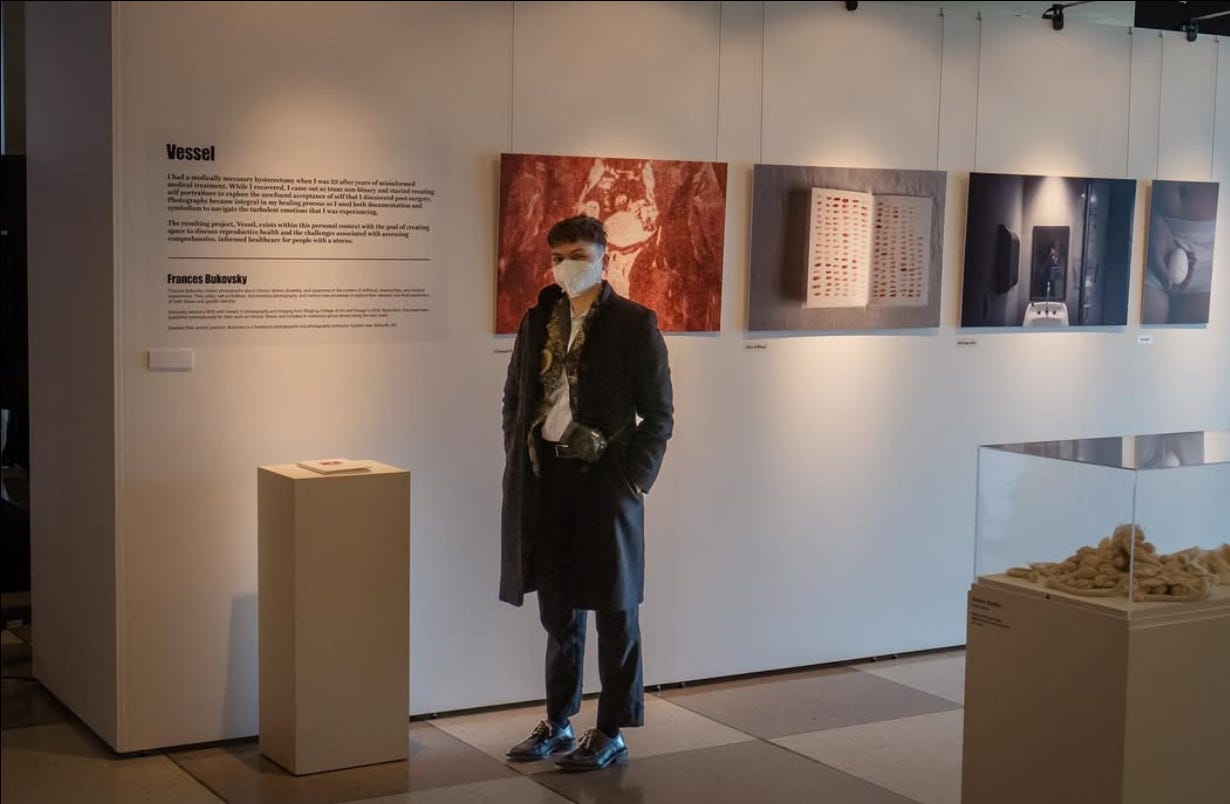

Vessel

Self portraiture, healing, and looking back at my first photobook 5 years later.

CW: Infertility, Medical Trauma, Blood

Where do I begin a story that is a spiral, one that began before me, one that will continue after me, my own experience being a point on a spiral that moves and writhes like an ouroboros connected to so many other things? How do I start to tell my own story when there is no defined beginning, when the edges of my narrative bleed through time, when I haven’t lived, or died, through the ending yet?

I can begin in the now, the time in which I still carry this particular story. I was recently in my prime care physician’s office, hip exploding with the monthly pain I’ve become accustomed to, it being the way my body holds time and the cycle of the moon as a swelling that turns to bursting. I wasn’t there for that reason, having given up on soothing my monthly ovulation pain some time ago, rather I was there for a renewal of my physical therapy referral.

The conversation after obtaining the referral began as an ask for pain relief-I told my doctor that I figured I’d bring up the pain, which had chosen that day to erupt, and I wasn’t expecting to resolve this particular issue, but rather would like to be able to sleep that night through the worst of it. The white of the room brought me outside of myself-I cannot help but dissociate in doctor’s offices, particularly upon mentioning the source of so much pain and bitterness, my reproductive system.

I had a total hysterectomy on January 22nd, 2020, preserving only part of my right ovary, part of it having been resected for biopsy and removal of endometriosis. The rest of my reproductive system was removed, adenomyosis, endometriosis, endometrial hyperplasia, and chronic untreated infections of the uterine lining having rendered my pelvis into a hostile land of inflammation and disease. With a family history of uterine cancer, a personal history of excruciating, debilitating pain even after removal of endometriosis, a history of suspicious biopsy results, chronic uterine infections, anemia, and a destabilizing experience of what I now recognize to be gender dysphoria, I chose a hysterectomy at the age of 23.

As I come into the 5th year since my hysterectomy at a young age, I know that there are other paths I could have pursued. I see the unfurling spirals of what might have been. In my PCP’s office, she talked through a couple of pain relieving options for me, mostly us discussing if I’ve ever had an allergic reaction or a positive reaction to muscle relaxers and if I’d like a short term supply. Then, she took a breath, and asked me if I’d like to stop my ovulation.

In the nightmarish hormonal hellscape of my late teens and early 20s, I had been put on a wide variety of hormonal birth controls and left to my own devices, waiting eagerly through the three month period for each one to see if my hormones would balance out. I happened to be one of the people who needed more careful monitoring, more precise management, and I spent 5 years fluctuating through extreme dissociation and a dissolution of self identity, enduring extreme side effects and hormonal imbalance.

I was encouraged to be continuously on hormones to control the irregular cycles, heavy bleeding, and unbearable cyst ruptures that landed me frequently in the emergency room. Endometriosis was a constant knot of barbed wire in my pelvis, adenomyosis a churning muscle spasm that would never release. Eventually, being prescribed a GNRH antagonist without monitoring by my doctor or a review of my health history resulted in an extreme mental and physical health collapse. My trust in the healthcare system has been irrevocably damaged by the doctors I encountered in my gynecological care.

My breath hitched as my doctor suggested stopping ovulation, and I practiced the grounding techniques I learned in trauma therapy as I felt my heart rate tick upwards. Though I’ve developed a positive relationship with my doctor, time seemed to slip and I felt like I was sitting in the uncountable chairs I have sat in before, about to be told that if I could “endure the side effects,” this pill would be the magic answer to the pain that left me unable to walk some days.

Then, she began to speak gently, explaining that she works closely with a colleague who has an expansive experience with creating hormone regiments tailored specifically to her patients. She went on to mention that this colleague primarily works in gender affirming hormonal care, something I had mentioned being interested in having a conversation about before, and so I could speak with her about my specific goals regarding hormones. To conclude, she said she absolutely would not stick me on birth control or hormones without careful monitoring and follow up.

Something unravelled, something was rewoven. I sat in my car after the appointment, golden sunlight illuminating the dried yarrow I keep on my dashboard. I didn’t sit in regret, but I saw a path bloom, a path that never was, but could have been. What would have happened if as an 17 year old struggling to manage my health, reaching out desperately to doctors for salvation, I had been talked to with such understanding, such consideration and care, and offered not a magic solution, but a toolset with which a doctor would work alongside me? What if I walked a path where I did not “fail out of treatment,” but rather came to a deeper understanding of myself?

This is a path that I recognize in its impossibility. As a late teen and early twenties, I was navigating the south Florida health system largely by myself, with health insurance that covered few doctors in my area, while managing uncontrolled mental health issues and undiagnosed health conditions. I didn’t know how to advocate for myself in the way I do now, I didn’t understand informed consent and the state of the healthcare system. As I sat in my car, I felt the grief of 5 years of immense challenge and struggle, and the relief of a cycle closing.

Vessel came directly out of my experience undergoing a hysterectomy, though as with much of my work, it is entangled in several experiences at once. The personal fuel that went into this book (I am ever grateful to nat raum of Fifth Wheel Press for letting me run with this series as one of the debut titles of the press) included not only my surgical experience, but the still very raw rage I felt going through the medical system and emerging feeling chewed up and spat out, my experience coming off of estrogen and progesterone based hormone treatments for the first time since late teenagehood and remembering in my body the trans/gender fluid identity that I didn’t have language for as a kid, and heavy themes of informed consent and bodily autonomy.

In making this work, I began to play with something that has become staple in my creative practice-the blending of documentary photography with self portraiture. Alongside Vessel, I had been photographing Where the Red Flowers Bloom, which was specifically about my experience with endometriosis. When I was diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia and made the decision to pursue a hysterectomy, I struggled with how these two projects intersected. I wanted Where the Red Flowers Bloom to be neat and self-contained, yet additional diagnoses complicated the ending, and I felt there was a shift happening in the work as I began to process internal experiences beyond the physical day to day reality of living with endometriosis.

Vessel became more metaphorical as a result, drawing from my life while introducing symbolism into it. Making the book was a lifeline, a way I could channel the anger that sometimes welled into uncontrollable rage that burned in my chest. The first case of Covid in Florida was announced while I was in the hospital for a hemorrhagic ovarian cyst, my first ovarian problem post-hysterectomy. While I was simultaneously dismissed and admitted for observation, administered drugs I felt coerced into trying, and then abruptly discharged, the world hurtled toward shutdown. I had a lot of anger, I had a lot of grief.

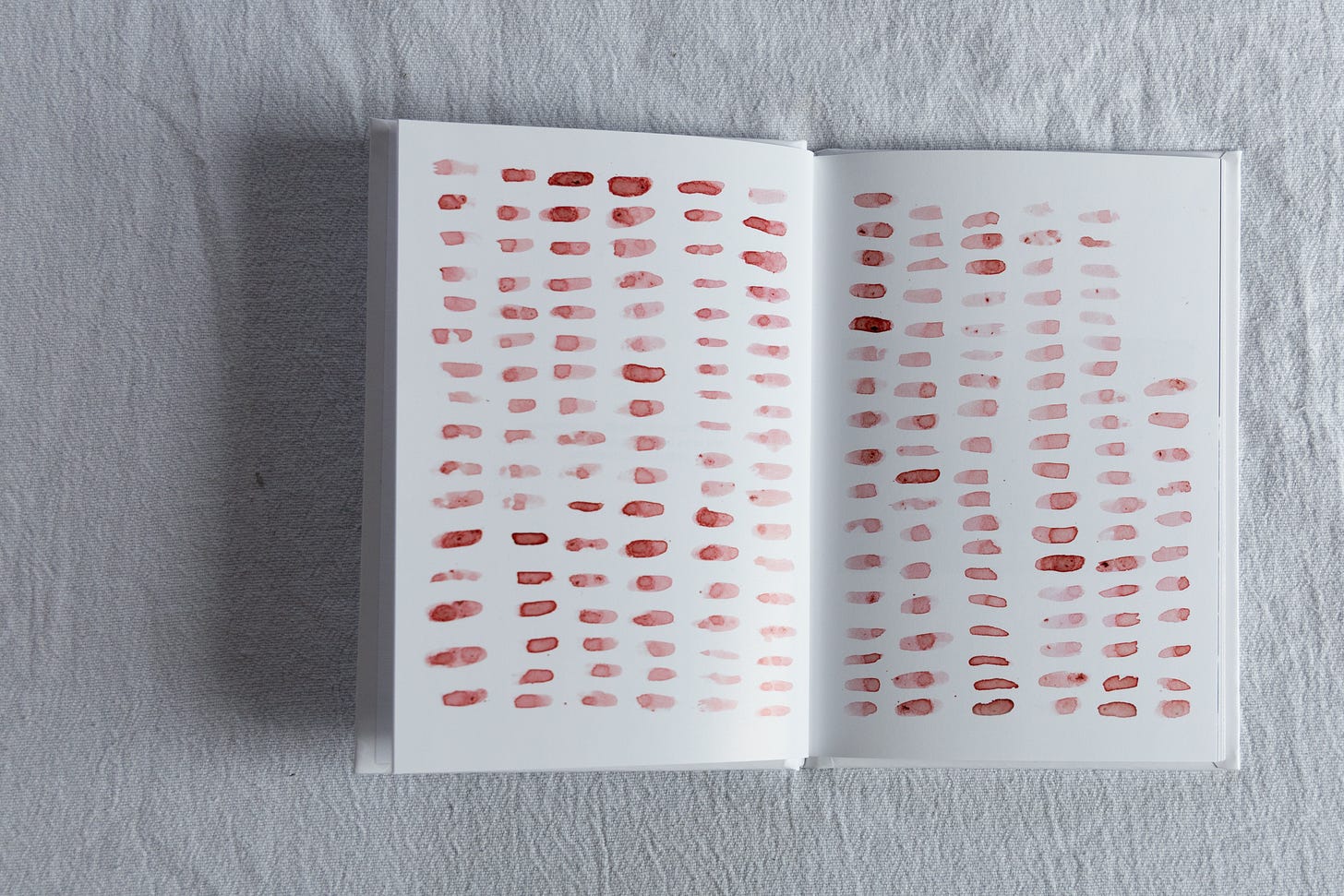

Something that marked so much of my experience with my uterus was blood. I unpredictably bled, frequently bled. In the beginning of the book are a tally of all of the days in the final year I possessed a uterus and experienced bleeding. An average person with a uterus bleeds for around 60 days a year, give or take up to 20 days depending on the length of their cycle. I bled for nearly 200 days, around 6 months that final year of having my uterus.

Reproductive issues run in my family. This would be something that would return to me later as I was diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, and could follow the threads of potential genetic cause through the symptoms of my family. My family on both sides are ancestrally Slavic, particularly Polish, Czech, and Russian, so I turned to beets for their rich red color, folkloric use in treating anemia, and connection to Slavic culture to honor the women in my family who have experienced so much reproductive grief.

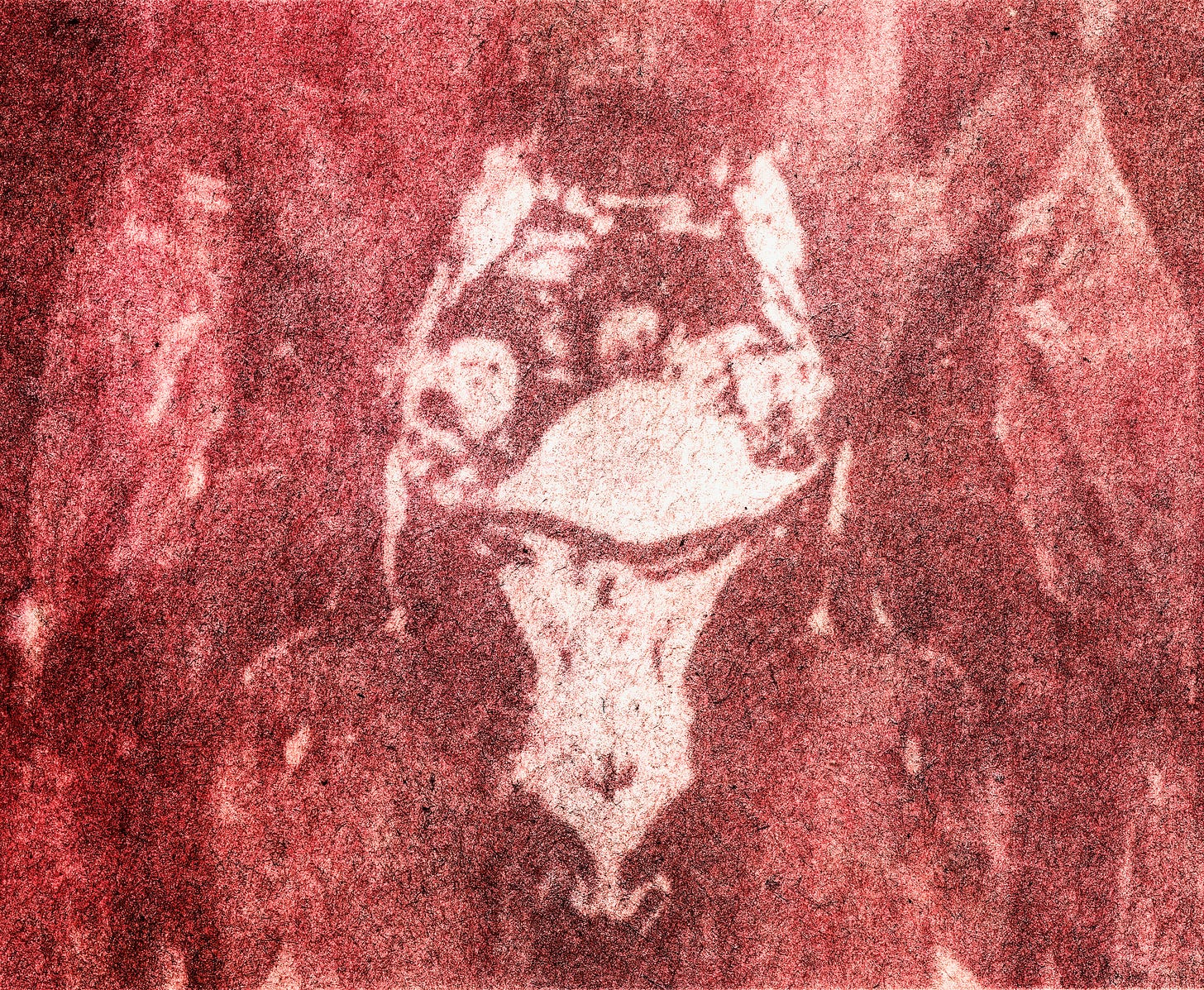

I used beets to create an anthotype of the last CT of my pelvis made before my hysterectomy for the cover of Vessel. An ovary is visible, the uterus tucked behind the bladder, hip bones of my somewhat narrow pelvis shadowy forms within the pink flesh of my thighs. The anatomy of my pelvis is forever shifted after surgery, ligaments reconstructed, organs removed or rearranged. For better or worse (though I overwhelmingly think better), there was a permenant altering of my body.

I also used beets in performance pieces throughout the book, enacting my rage and my healing. While I photographed these, images made huddling in the corner of my room in my parent’s house, the place I moved to when I became unable to take care of myself while ill, I felt the grief of my experience in the medical system. I was able to take the shame, the grief, the anger, and make it manifest externally, somatically moving it through the wringing of beet juice through my hands, the pouring of it over my face, the shock of cold submersion beneath chunky, earthy, viscous solution.

Much of my anger revolved around the loss of autonomy I felt throughout the years. I was seeking care from OB/GYNs who I wish had admitted to me that my case was too complex for their practice and had not projected their expectations onto me. While I am also surgically sterile, I am child-free by choice for many reasons. I have known from a young age that I did not want my own biological children, and I have not ever felt an explicit call into parenthood. I feel fulfilled by bringing care to those I work with as a care worker, by tending to family when I can, by connecting with others.

Yet, the primary concern when I reached out for help from OB/GYNs was my fertility. I expressed over and over that I wanted to get to the bottom of my symptoms, that I wanted more aggressive treatment if it meant a shot at a cessation of the decline I saw happening over several years, that I did not want to prioritize my fertility when coming up with treatment plans. I was repeatedly told that I was “too young” to make that decision, even as I lived independently as a 22 year old, that I would have deep regrets if I caused myself to become sterile or infertile, and was accused of setting up a situation to sue a doctor later in life. I was told to have children early, despite not being financially, physically, mentally, or relationally stable. I was told that my ovaries “looked good,” so I should “use them before that changed.”

The irony, and what grieved me most, was being handed the pathology report after my hysterectomy that indicated that I would likely never have been able to have children. My ovaries contained so many cysts, so much endometriosis, that pregnancy was unlikely. My uterus was so inflamed and had enough significant pathology that it was unlikely to have been a suitable environment to bring a child to term.

Decisions about my care were made on my behalf for a future that was highly improbable and unwanted. When I spoke to my surgeon for the first time who ultimately did my hysterectomy, her concern about me pushing for organ removal was centered on my well being as a young person. The shift was shocking, my nervous system which had been gearing up for another debate about my lack of desire toward parenthood suddenly encountered a doctor who cared about me as a person, not a potential mother.

When things changed and a hysterectomy became a treatment path, that same surgeon held my hand while she talked through some of the risks I’d be facing if I decided to proceed, and gave me a list of resources of not only information about the surgery, but communities I could connect with to talk to other people. She laid out all of the treatment options, gave her opinion on which she felt most confident pursuing when asked, and reassured me that I could change my mind at any point leading up to surgery.

I cried in the car after that appointment, not so much for an uncertain future (that would come later), but for experiencing true informed consent and agency in my medical experience. Up until that point I had experienced a lack of guidance, a previous surgeon who had misrepresented his experience in the particular surgery he was performing and had given incorrect medical information to me, who had left an infection that was clearly active in a pathology report untreated for over 6 months, been repeatedly dismissed by emergency room doctors, and in general possessed a lack of understanding about not only what was happening to my body, but paths of treatment.

In the book form of Vessel, I list out the treatments I had tried, the symptoms I was experiencing, the triggers and allergies that seemed to elicit chaos in my body. The images are visceral, my hormonal acne pressed against a piece of glass, my abdomen after surgery, belly button kept from unravelling by surgical packing, reopened scars from the laparoscopy, a piece of flesh lowered into the earth, a knife embedded into a beetroot.

The further away from 2020 I get, the more I see how difficult this work is to look at, the pain that is in it, the anger. I also see the moments of softness, the curve of my side with sand stuck near a healed scar, the edge of my ribs with the mole that I share with my mother, cradling a determined regrowth of bok choy that is both rotting and unfurling. When I teach self portraiture as a way to hold space for the parts of ourselves that we may not want to look at, I am thinking back to the way making this book helped me create space for the grief that shaped me into who I am today.

Photographing saved me in the sense that it gave me something to put the emotions that have at times threatened to consume me. It has also brought me connection and community in multiple ways. Sharing this work with others has always led to meaningful and intimate conversations, ones that open space to heal shame and isolation. When Vessel was shared as a part of Wanted: A World for One Billion at the UN headquarters in NYC, I remember a woman who breathed life into her own story to me, a story she said that she had rarely shared before, but that she felt less alone having shared it.

Beyond having conversations about this work, developing this series led me to more intensively begin studying disability studies and Disability Justice, which contextualized so much of the experiences that I’ve had in the medical system. Viewing what I’ve gone through within a systemic perspective removed the isolation for me. Suddenly I was not an individual alone sitting anxiously in a waiting room, but I was a member of a community navigating shared experiences. It also allowed me to connect to other artists working in illness and disability and forge connections that have led to incredible friendships and conversations.

This is a story without a conclusion. I am still alive, and I experience the world through an ever shifting body. 5 years out from my hysterectomy, I still don’t regret my decision-it appears to have been the right one for me in the context of the situation I was in at the time. I feel at home in my body, more attuned to the cycle of my hormones, more deeply seated in my flesh.

My hysterectomy was not a magic wave of the wand. I still have cyst ruptures, live with chronic pelvic pain, and am currently learning ways to manage pelvic dysfunction that my hysterectomy has undoubtedly contributed to. Yet, I am alive, something I was unsure would be true for long prior to my surgery. I still don’t regret not having children, even as I approach 30, and feel mostly fulfilled in my life. My health has stabilized after many years of connecting the diagnostic dots and creating safety and stability in my life as a whole.

It has taken 5 years to be able to write about this book without slipping back into anger or unmanageable grief. I am incredibly grateful and in many ways privileged for the healthcare I was ultimately able to access, and am fearful for the present and future of gynecological healthcare. Informed consent and bodily autonomy are a right, and having lived through the consequences of what happens when those values are not upheld, I am committed to working for a future where all bodies are respected and honored regardless of race, gender, reproductive status, age, and ability.

I continue to live through these spirals of complexity, learning more and more about the interconnected ways that health, our environment, and the systems we live in shape us. Making Vessel was a process of grief, of loss, but also of creation and discovery.

This is *a lot*...to take in, to relate to...to want/need to spend more time with. I truly appreciate seeing & reading how you processed then & are processing now, in visual ways, emotional ways & the reflections you articulate with the passing of some time. Adjustments are ALWAYS. Does this book exist somewhere to hold or view? Too many comments & questions for this space but would love to talk abt this work further.